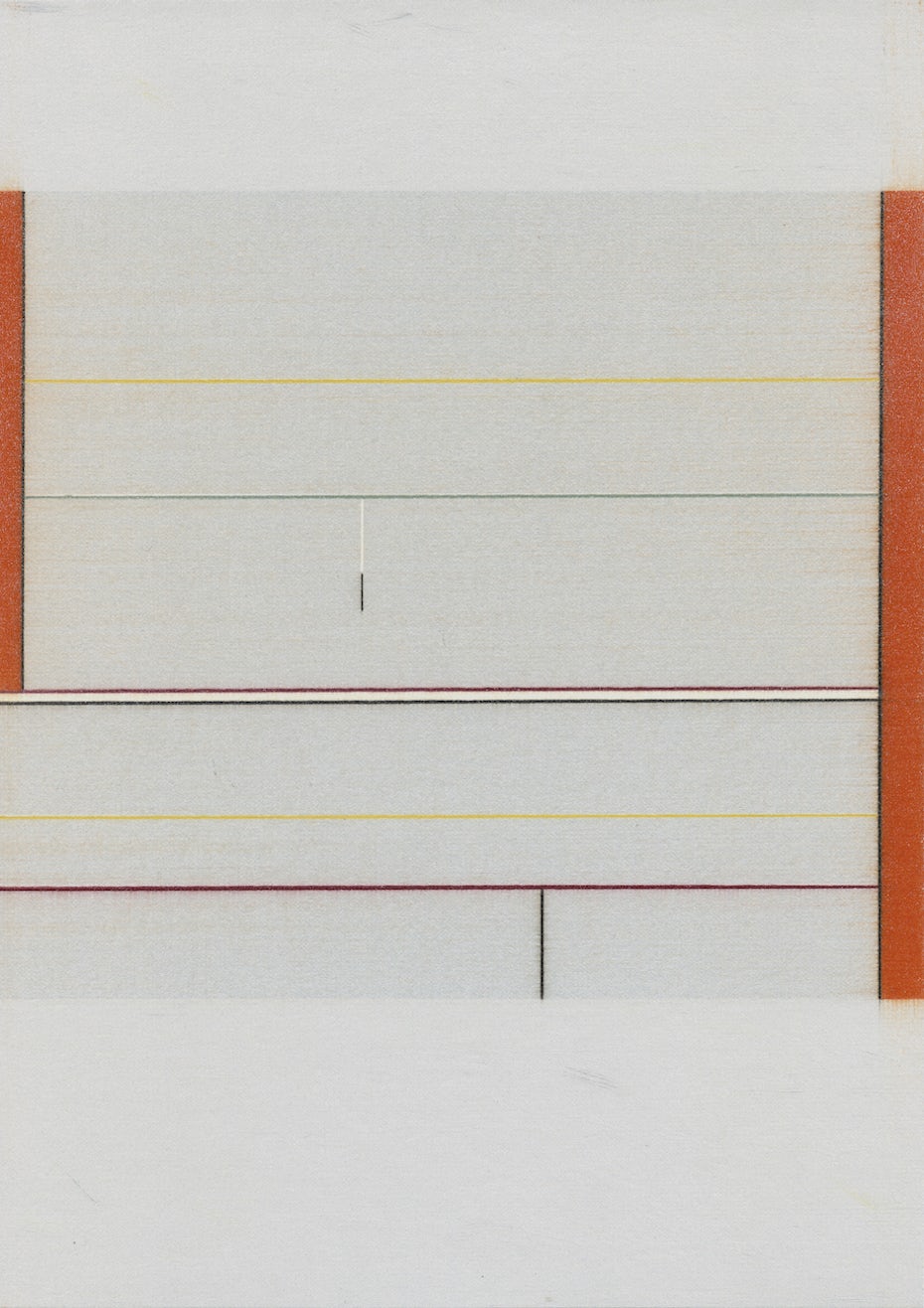

‘Les très riches heures de Jean Le Sauvage’

Johan De Wilde

Brussels

07.09 - 21.10.2023

Works

Installation views

Press release

From a conversation with Derek Højbjerg-Twaithcombe, Oslo, spring-summer 2023

(sometime during preparations for the exhibition Les Très Riches Heures de Jean le Sauvage)

JDW: … and that is justified. Don’t ask me anything about technique.

DH-T: I promise, but how long do you work on such a drawing?

JDW: A long time. My age plus the necessary time. Come on Derek, ask a serious question.

DH-T: Does your work actually mean anything?

JDW: I can add as much information to a piece as I want later; it really doesn’t make the image better or worse. So the answer is: I only ascertain. Please don’t address me so formally.

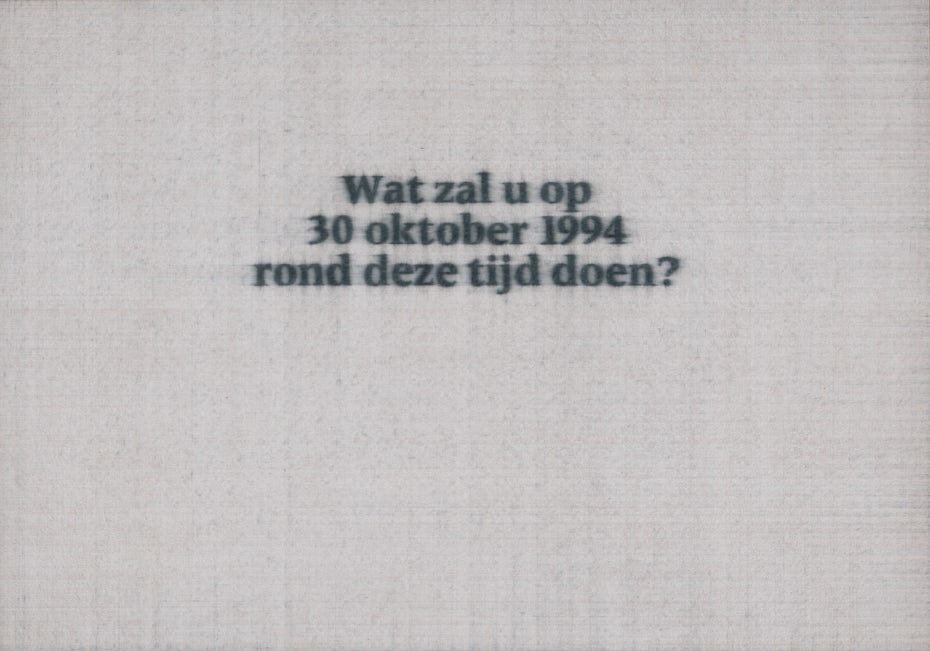

DH-T: Very well. Tell me, Sauvage, why isn’t your work more uplifting?

JDW: Oh, perhaps it’s comforting enough. You have to remember that overview and synthesis are never within our reach, however much we want them to be. You can make bread out of flour and art out of chaos, but man is fundamentally lonely, and in the end he loses out. Although man’s loneliness is a sign of hubris. We are somewhere in the soup of time (millions of years after us, millions of years before us) and as a coincidence we have no equal. I find this thought very encouraging, much more encouraging than the idea of a God or the delusion that nature is preoccupied with our fate. How do you translate something like that? Take, for example, Al wat geweest zal zijn – Tout ce qui aura été. A series of 1440 drawings – call them illuminations. Every minute of the day in its digital form, a constant memento of a past world. For every generation knows its past world. An endless parade of ‘it used to be better’, which would be tantamount to saying that everything has got worse since the first ‘used to be’, which is nonsense. That’s why the work looks both forward and back, without nostalgia, time detached from chronology, an ode to imagination, energy and grandiose deviance. It also has a poetic title. Imagine all the images, including those of imaginary events that never happened. All the flashes that the viewer remembers or dreams. I know some people claim that nothing flashes through the viewer’s mind, that they don’t think at all. Earlier, for example, I drew the word ‘Oslo’ and wondered what image someone who had never been to Oslo would create. This imagination is fantastic, but it’s also the basis of many misunderstandings. Just look at ‘Dresden’, or the images that emerge from ‘Mariupol’ or ‘Moscow’. I digress.

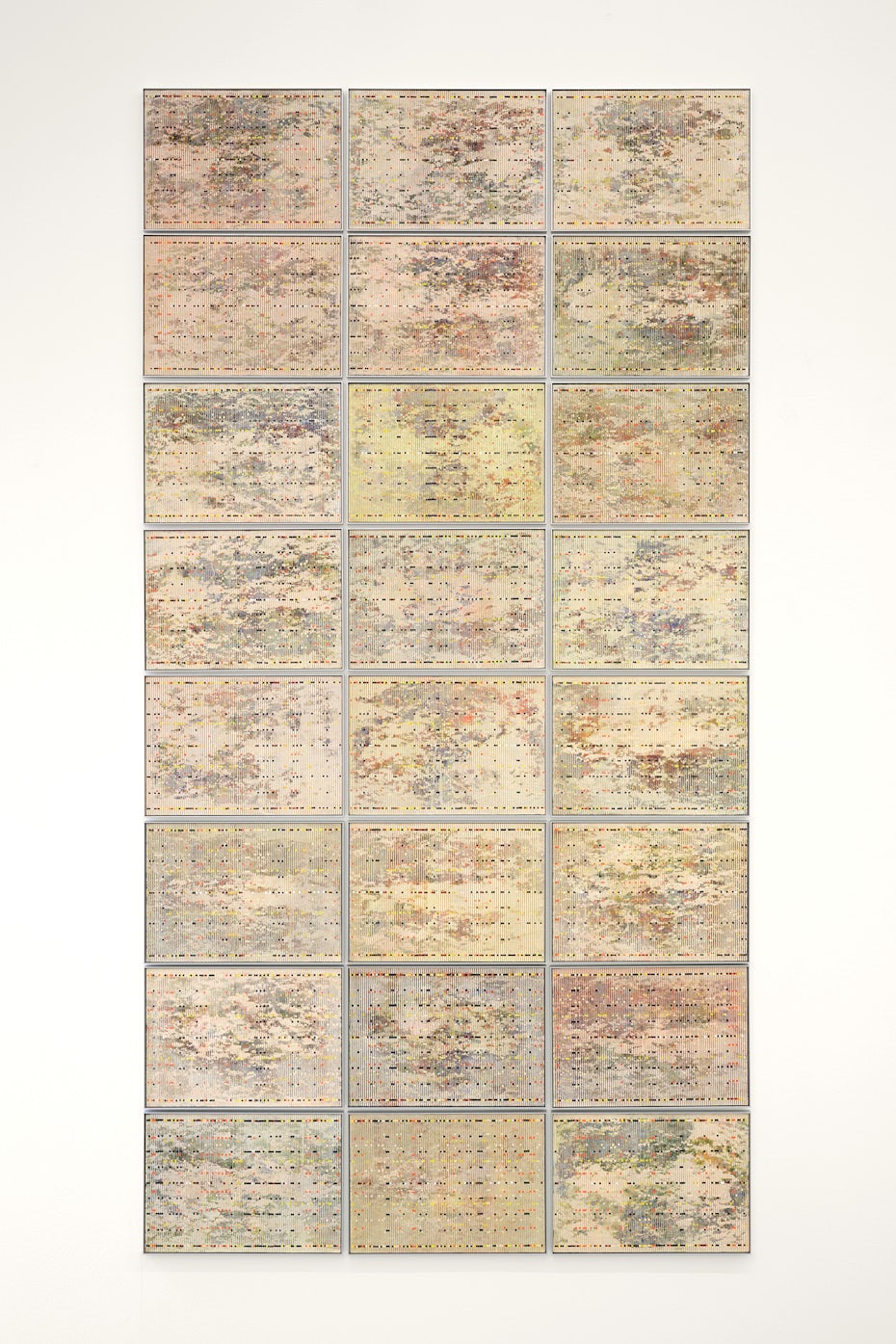

DH-T: Al wat geweest zal zijn… your own Très Riches Heures?

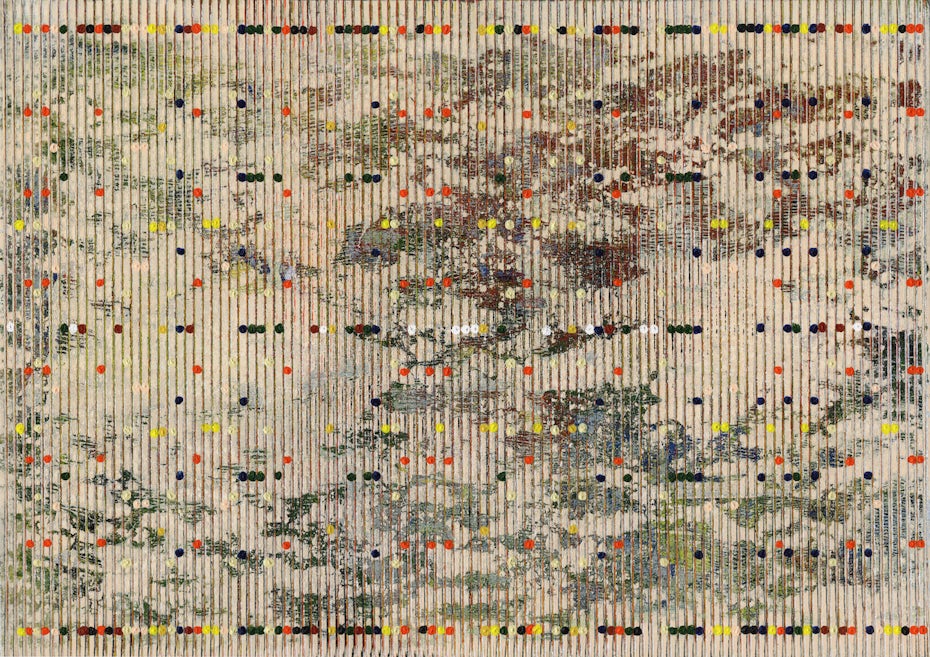

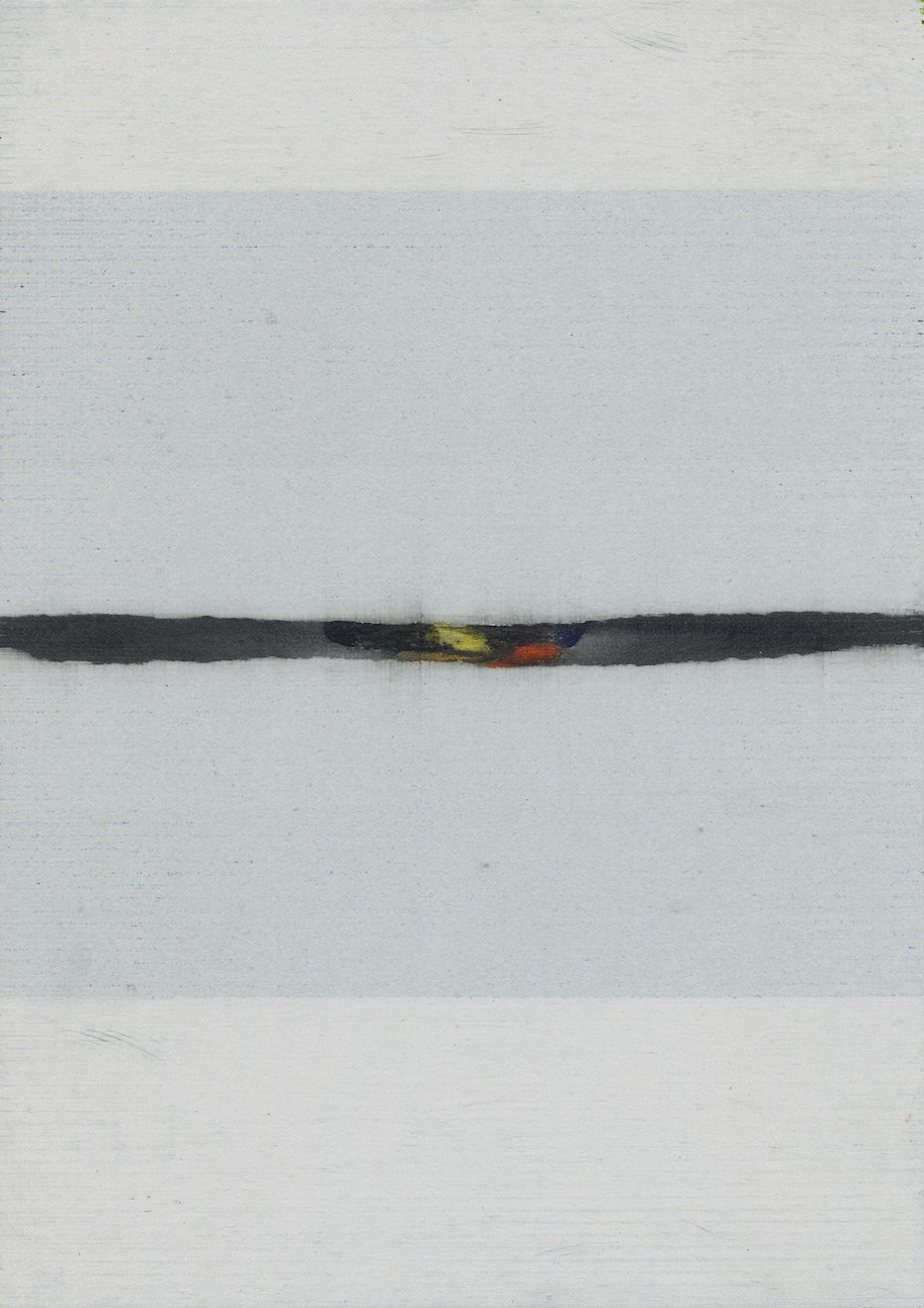

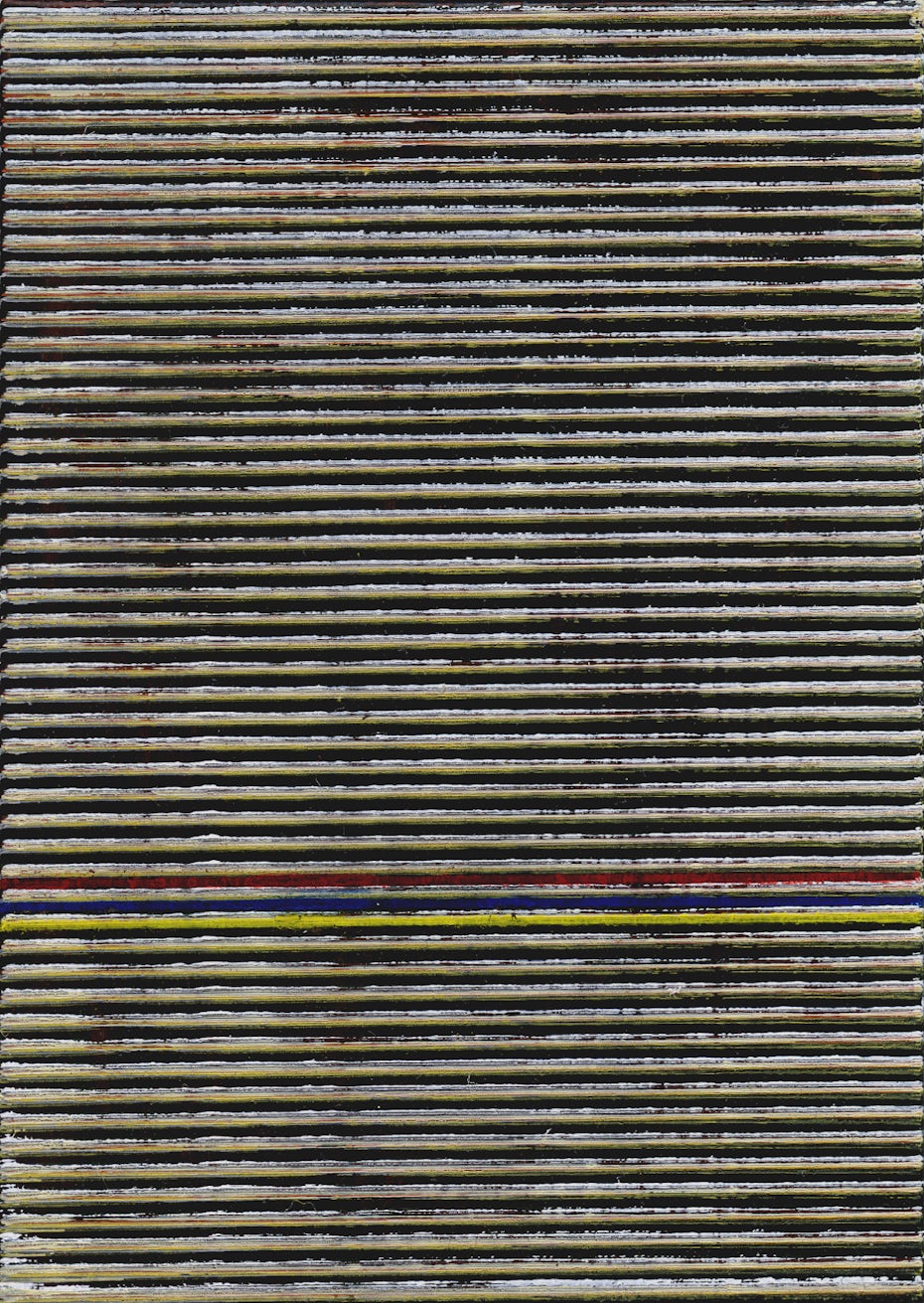

JDW: (coughs) If you like, you can take the title literally. My works are created in a prehistoric inertia in which every action, every pencil line, every new layer is a unit of time. A lot of people would say that’s ‘completely outdated’, but that’s nonsense. As I said, everything keeps being better in the past. ‘Completely timeless’ would be a better description. But that, too, is nonsense. These works only have meaning if they are handmade. More than that, if they are handmade by me, not by an assistant, not ‘made in somewhere’. They are my ‘History’ and I want to make them as universal as possible, a collection of what always and never recurs simultaneously. The event ‘you brush your teeth on 15 May 2023 at 6:45 a.m.’ is immediately gone forever, instantaneously generating a future and a past. Multiply this by the number of people… I deliberately translate this on a universal scale of A6/A4/A2. Of course, one is allowed to think of the Van Limburg brothers when looking at Al wat geweest zal zijn – Tout ce qui aura été.

DH-T: The world has once again opted for chaos. No one, not you, not me, seems to actually be responsible. All parties involved are, by their own admission, brimming with innocence. And the saying ‘the first casualty is the truth’ comes to mind. How does your History series respond to this?

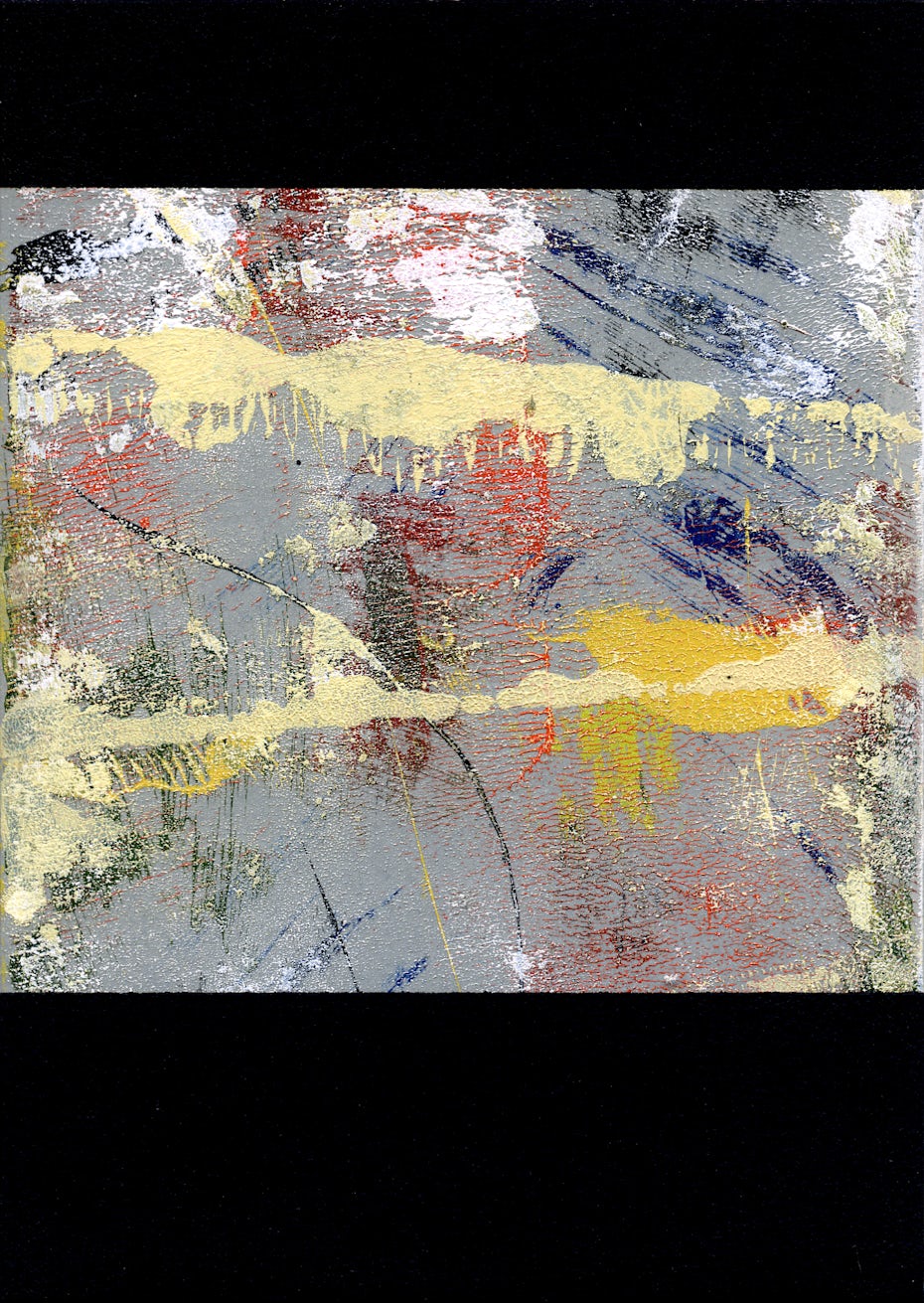

JDW: Every human action is a translation of what someone knows, thinks they know, doesn’t know, sees, doesn’t see and thinks they see. So where is the truth? This is precisely how all my works translate. There is conflict, war, unrest and misery. Many dance on the volcano, which is nothing new. I prefer to translate indoors, in the privacy of a studio. I’ve invented the term Indoor Impressionismus for this. It’s as anonymous as possible and without any sentiment. Again, nature’s indifference is oppressive, but part of a clear agreement. Humans are essentially tolerated, but our presence is not necessary. I almost said superfluous. The incomprehensible thing about human beings is that they cannot or will not see this, and therefore commit a breach of contract. On the other hand, how could it have been otherwise?

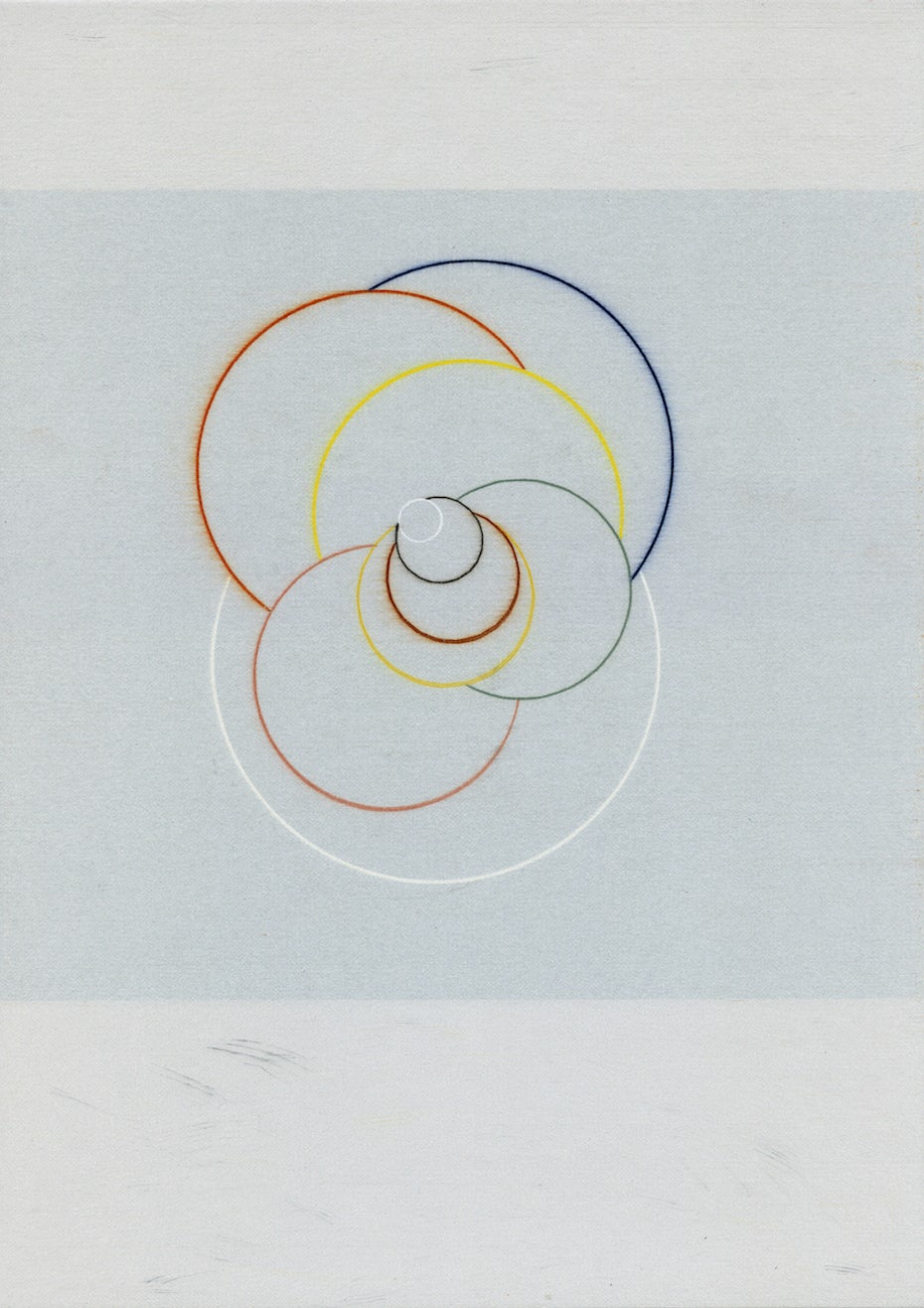

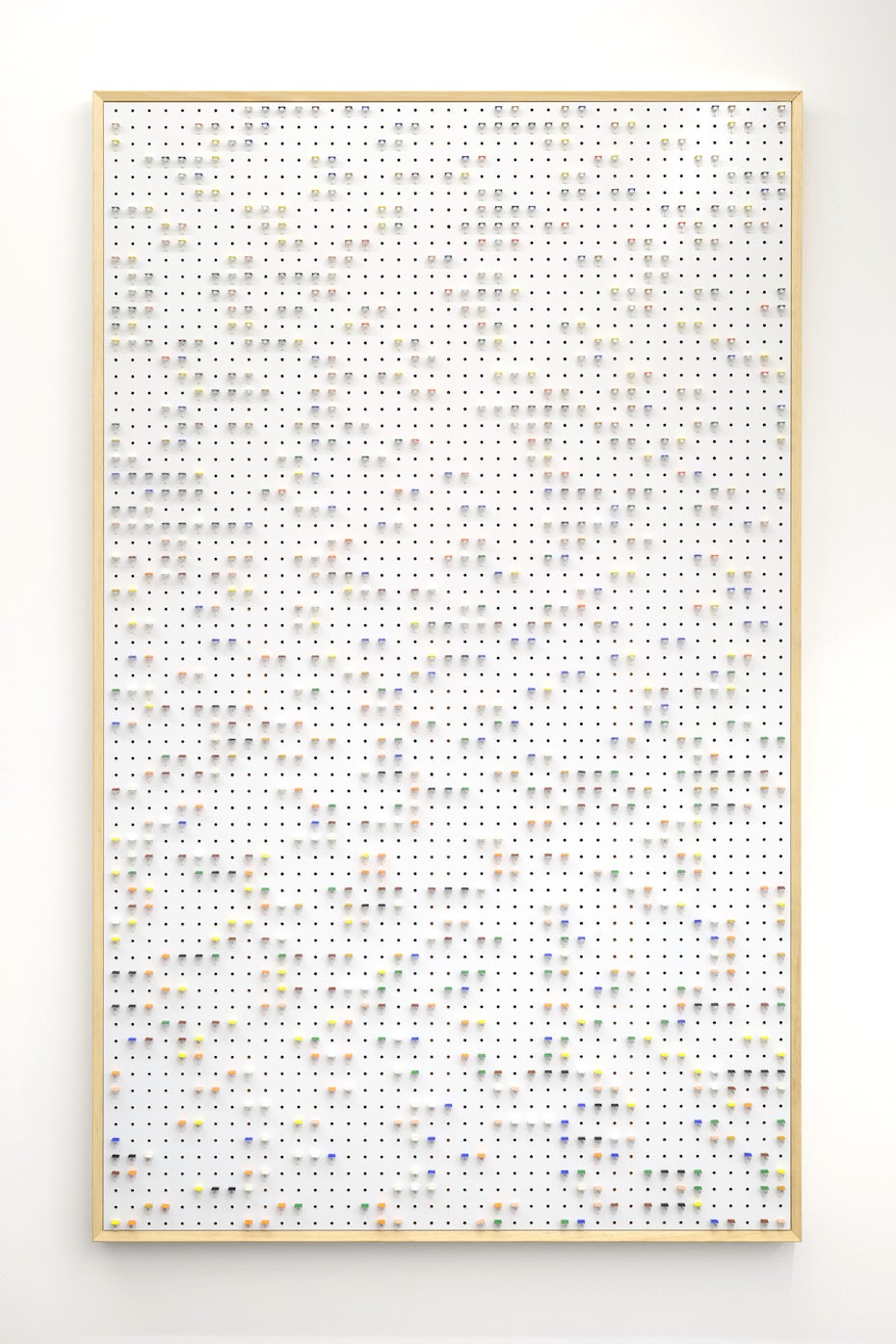

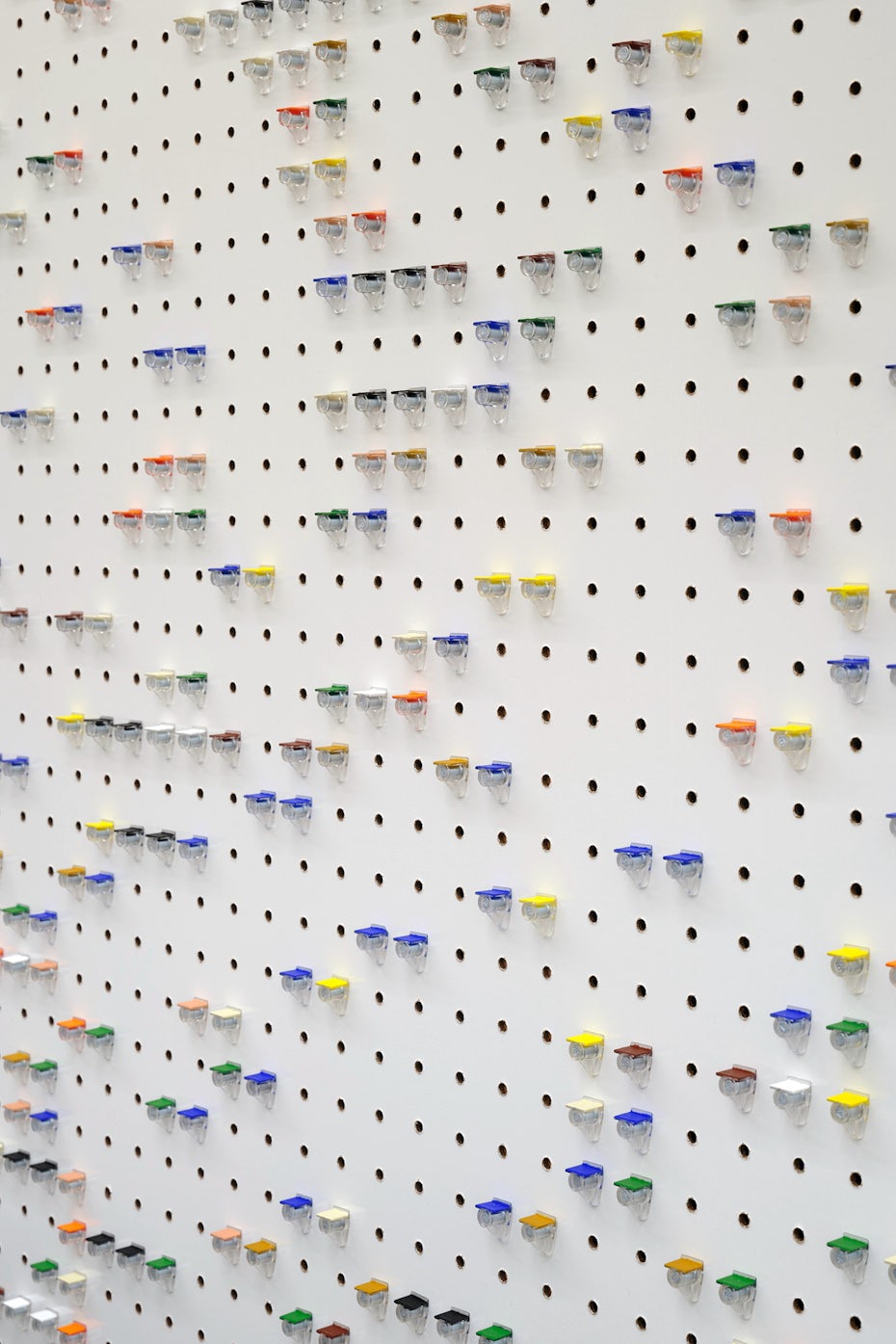

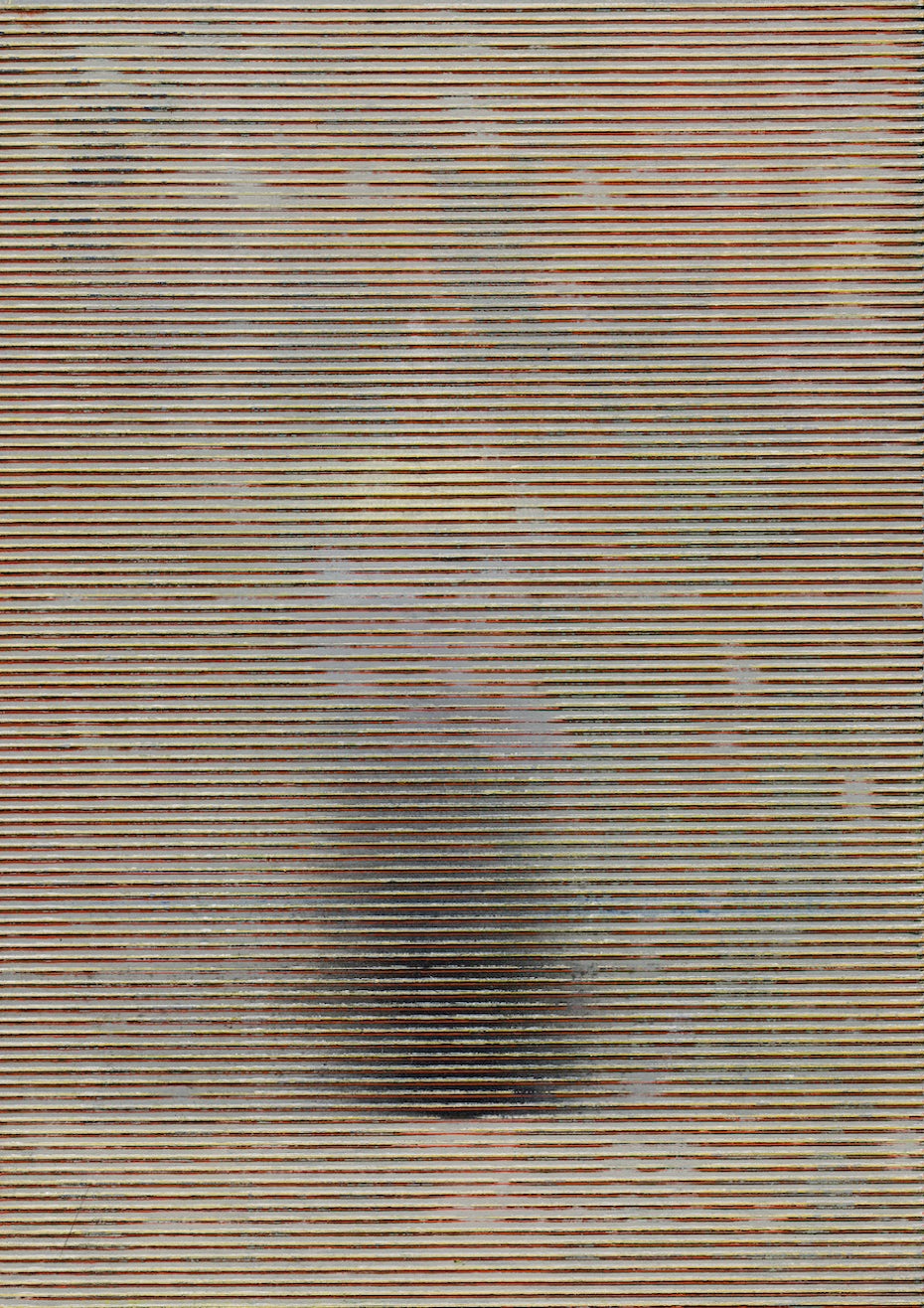

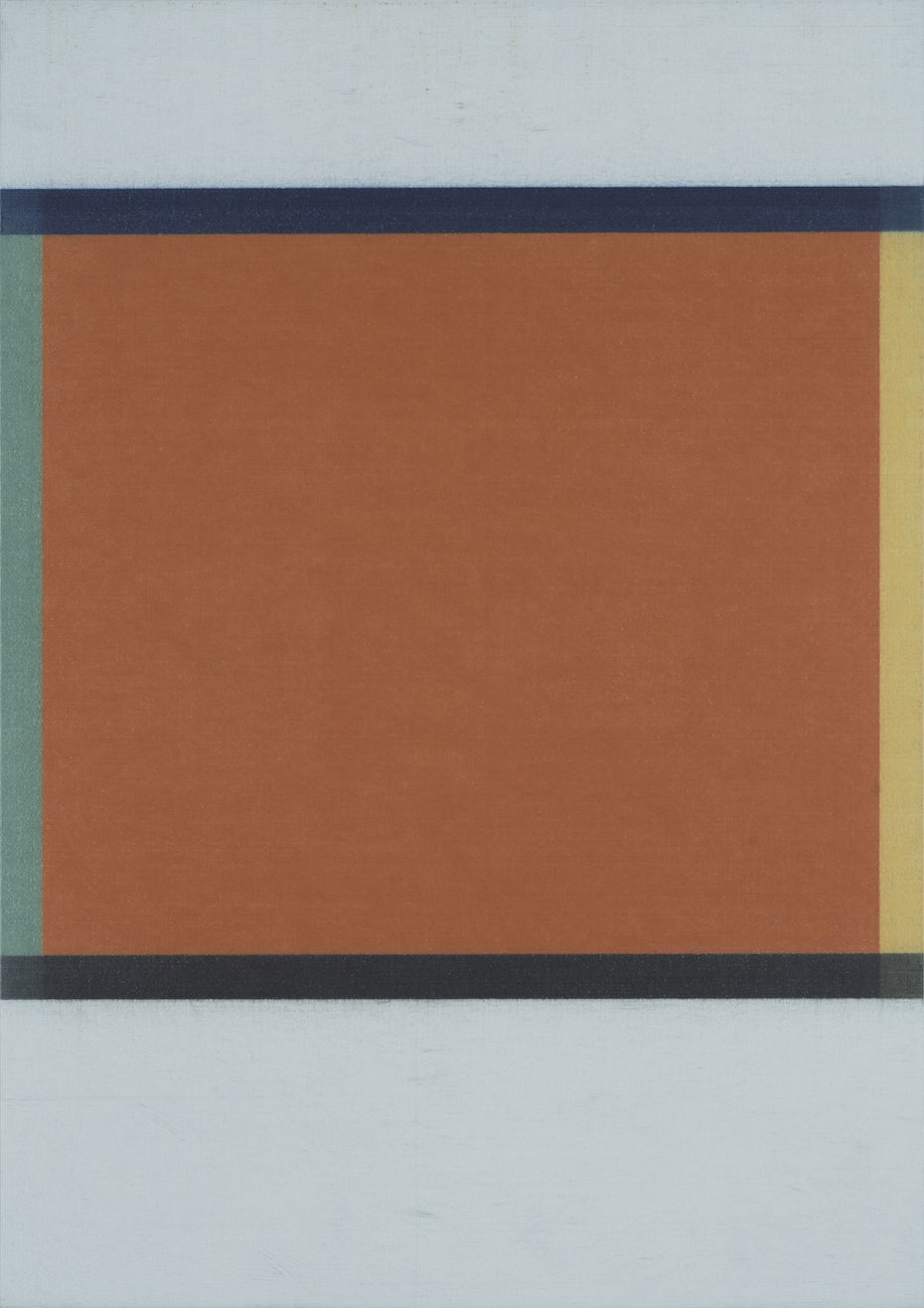

How could humans have organised their sojourn differently? Without Peloponnesian, civil and world wars? Without all-consuming, runaway capitalism? In that case, magnificent works of art might never have been created. We are perpetually at a fork in the road, forced to choose a direction. A translation of this could be Pi of De val der engelen. Every perspective is present, but without a trace – up is down and left is right. Do you look at a map of the world? At clouds? At a plan with coloured satellites in battle formation? At a tapestry? It dizzies like in Frits Van Den Berghe’s beautiful, swirling and almost violent De val der heiligen (Museum of Fine Arts Ghent), which, incidentally, was more or less the model for my Pi of De val der engelen. Ironically, Pi offers some structure. It’s legible, with a colour for each decimal, and the first part, with 24 pieces, is exactly the same height as its creator.

DH-T: Hence the nose?

JDW: Indeed. It’s helpful, and perhaps necessary, to start an exhibition with a ‘measure of things’. In this case, the measure of the creator. This 176 cm dictates the entire exhibition, both horizontally and vertically. The space around it is many billions of times larger, and that’s a mismatch. The form of the exhibition is another doomed attempt at synthesis.

DH-T: Greed?

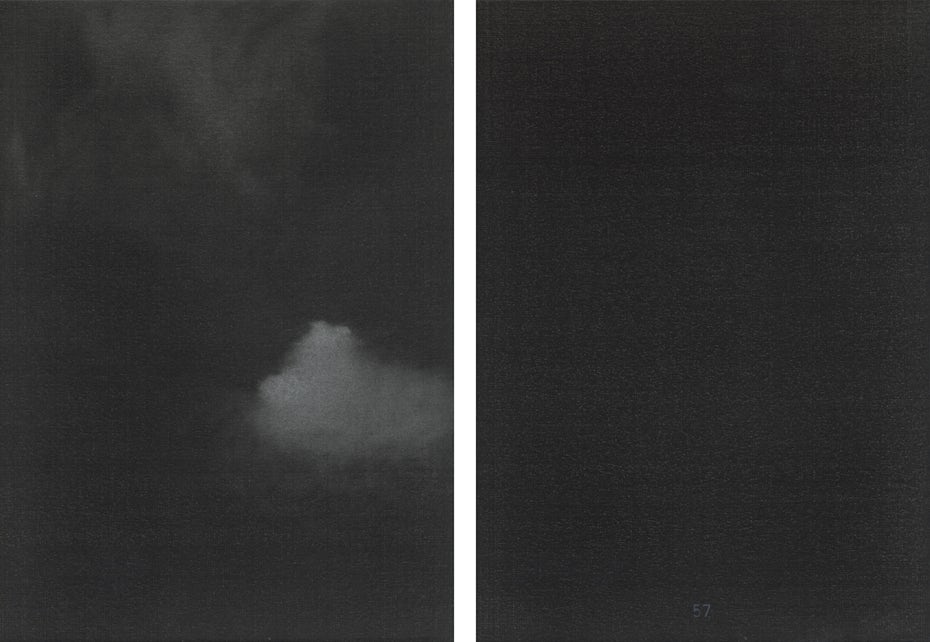

JDW: Exactly. As I often do, I wanted to work in a field completely devoid of any context and, in this case, insert the human trait that I think causes the most misery. It’s an observation drawing. An observation in graphite, without judgement, without comment.

DH-T: ‘Maniera’, ‘Val der engelen’ and references to Fra Angelico’s frescoes in earlier works: don’t the ravages of time leave you indifferent?

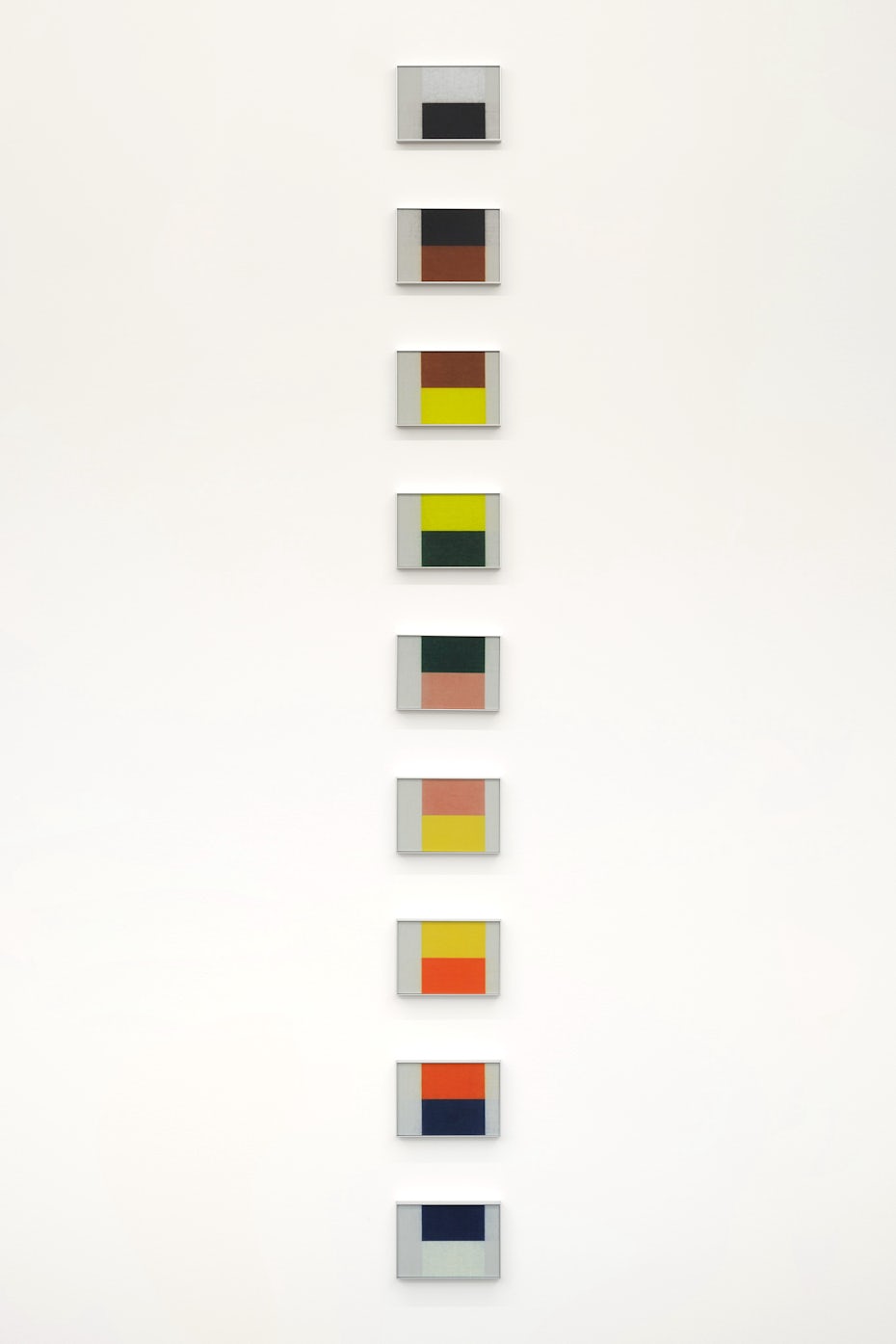

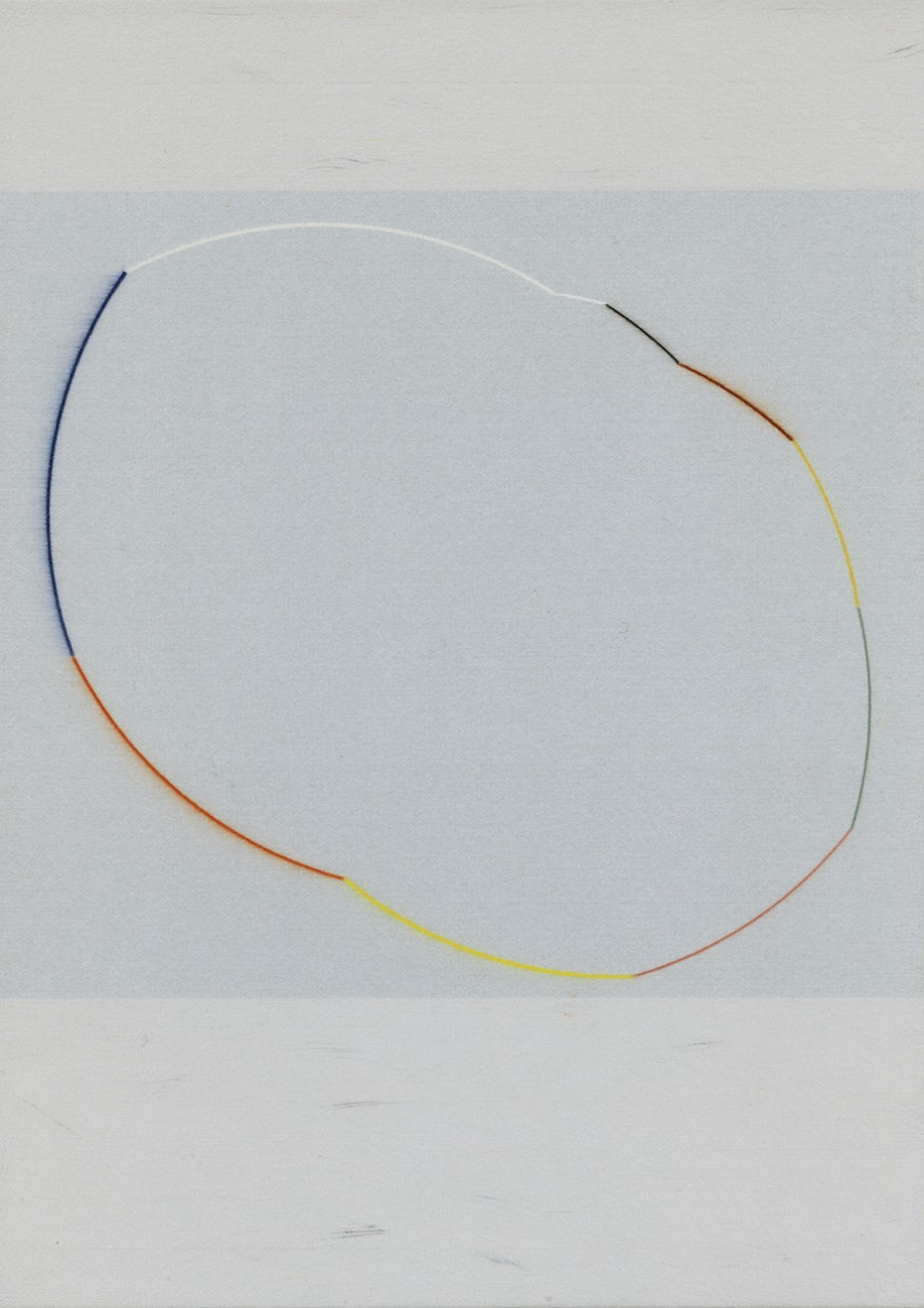

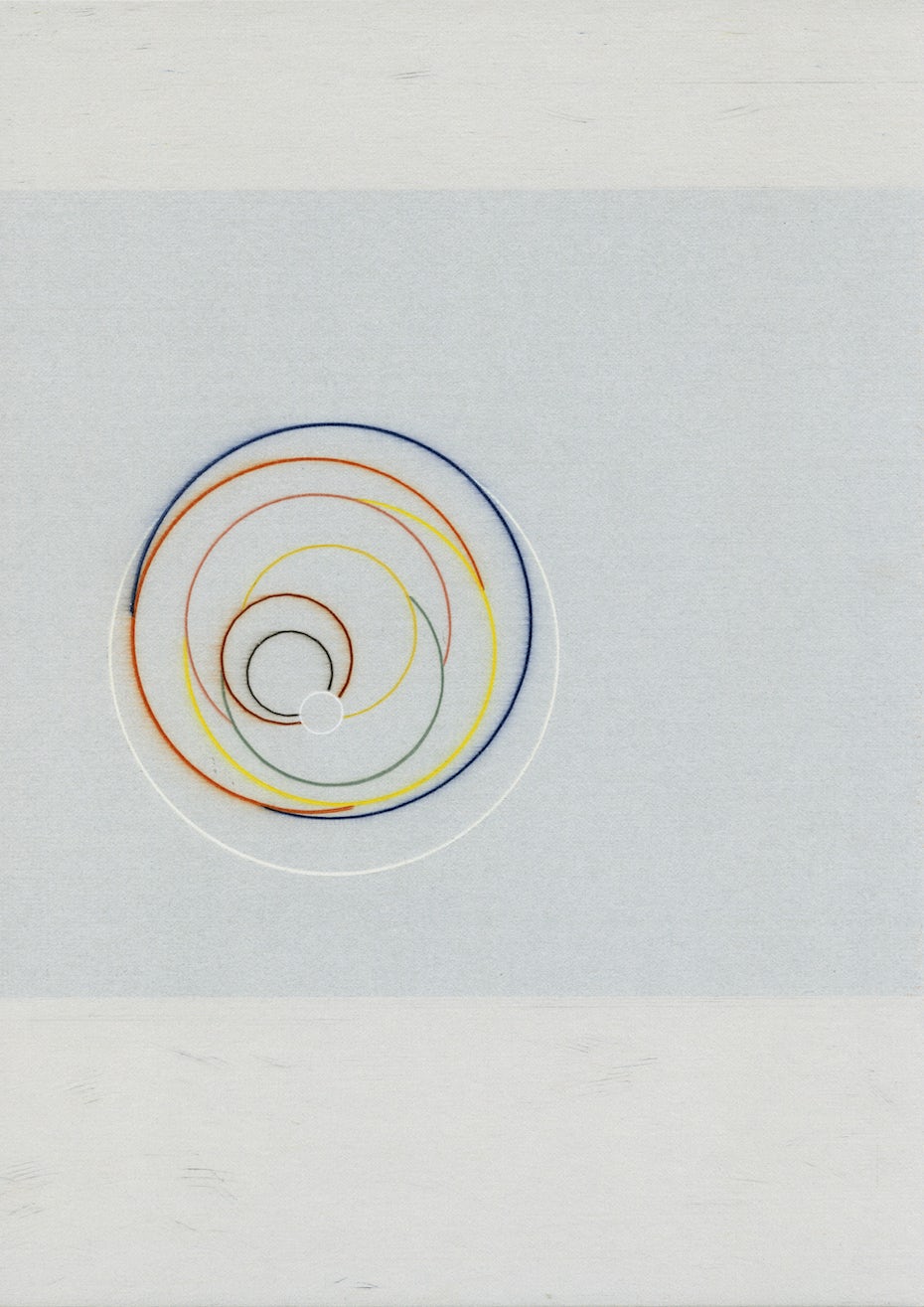

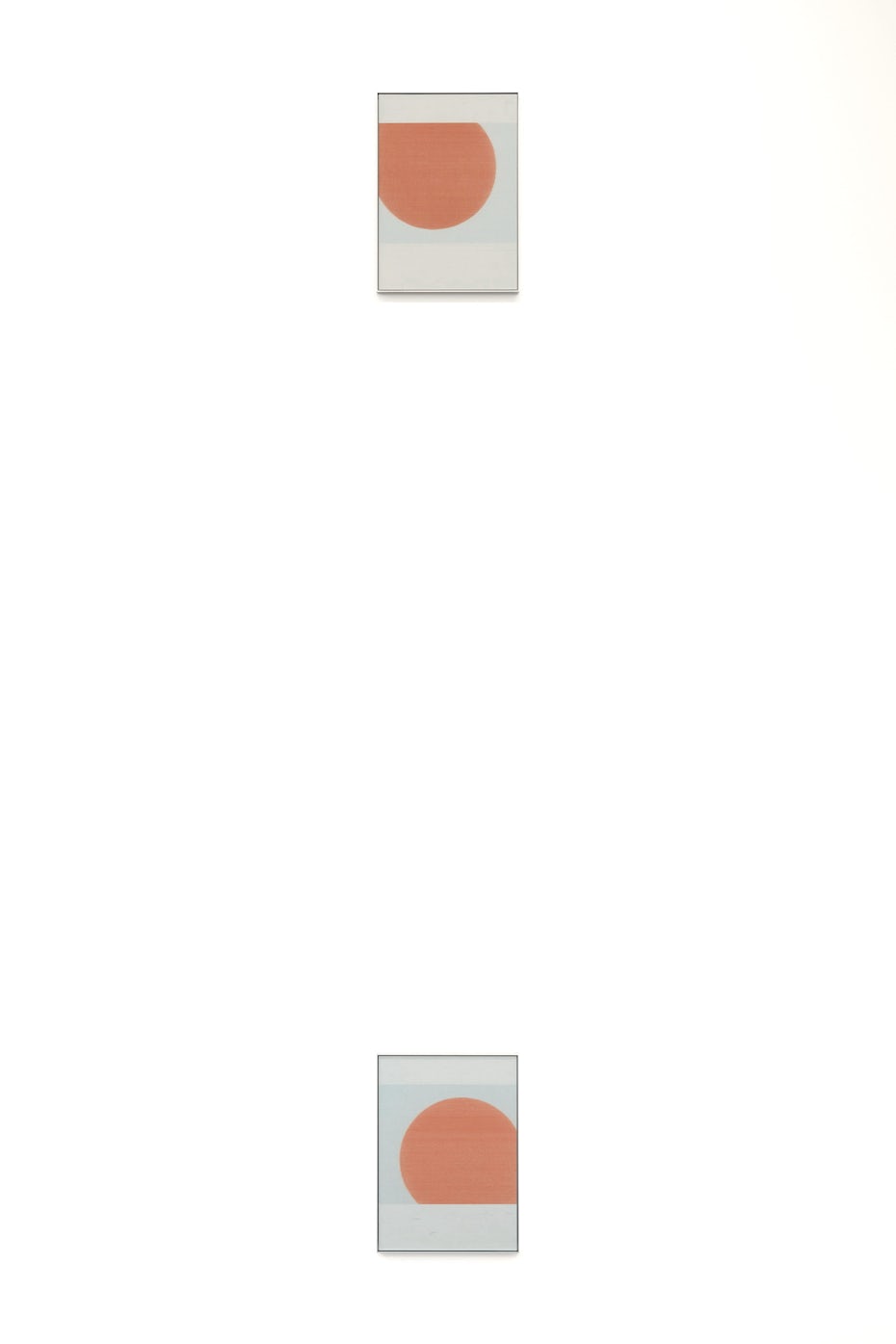

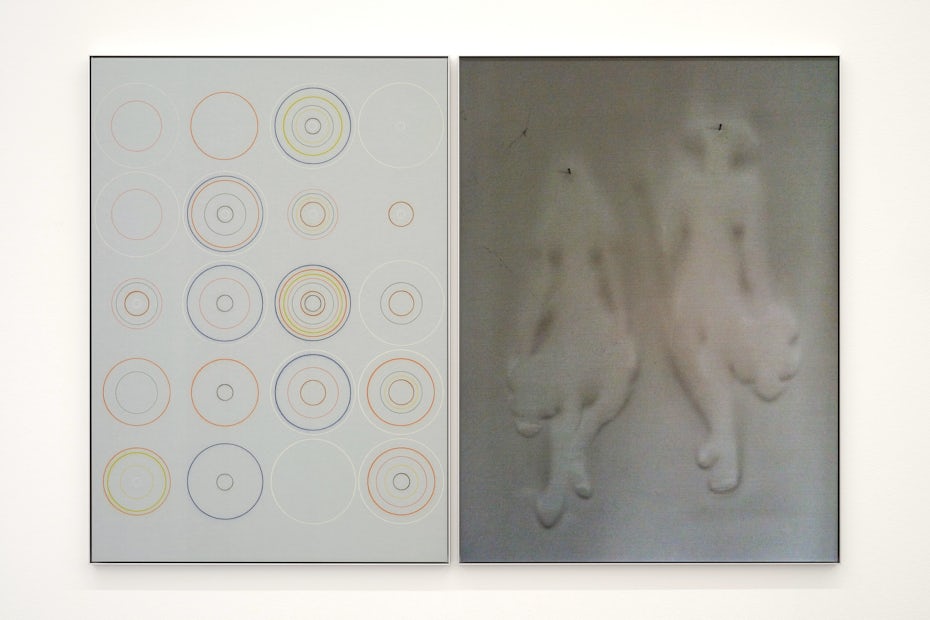

JDW: Maniera was originally going to be called ‘Renaissance’, but the term ‘Maniera’ also includes ‘style’ and ‘mannerism’, which has an ironic ring to it. Maniera suits this juncture better. The Venus de Milo may have preferred to remain undiscovered under the earth, but now that it’s here and I’ve seen it in the Louvre, it’s become history. I cannot help but associate it with myself. I have a scale model of it in my studio. In other words, I cannot help but translate it. This happens associatively, at lightning speed. I think of Hodet, a work by Markus Raetz on the island of Vestvågøy, then the midnight sun, Pi and finally, a circle. This is how the ingredients for the 10-piece work come together. It’s not like I sat down and decided to make Venus spin like a doll in an entertainment world on top of a coloured circle behind a screen of ten coloured lines. But I did keep in mind that the silhouette seems to look at us and then averts our gaze. Ten times we see a different form, at once abstract and amorphously figurative, balancing perception and thought, spinning endlessly. And the ravages of time, well, in my opinion, there’s nothing more beautiful than the deterioration of a fresco. I can think of no more poignant metaphor.

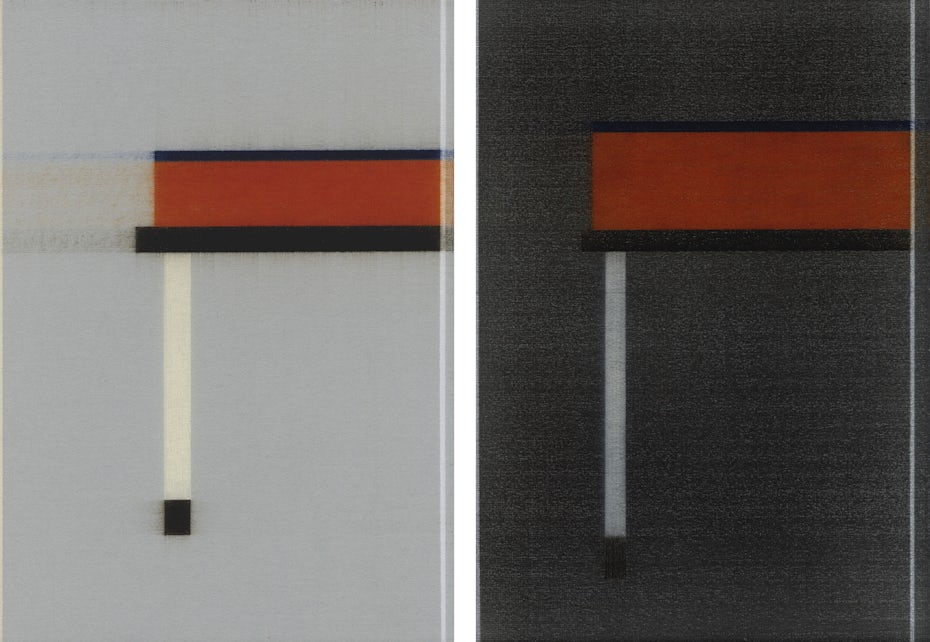

DH-T: Les Très Riches Heures has plenty of room for your favourite topics: Pi and ‘sunset’.

JDW: As I said, there is a mismatch between man and the universe. It’s not just a question of scale, it’s also the use of language. We say ‘sunset’, but the sun doesn’t move. Yet you ‘see’ it move. No matter how scientifically explainable the phenomena, this conundrum cannot be solved. I try to contrast Pi with it in a different way each time. For example, I try to twist the perspective by dividing the disappearing sunlight into ten stages. I see Pi as a 21st-century cave drawing, a gesture made out of awe. I also think of all my drawings as interconnected palimpsests.

DH-T: You talked about freedom some time ago…